Rebel Threads: The Subtle Violence in Comme des Garçons Stitching

Fashion has always been a canvas for rebellion. From Vivienne Westwoods punk-era bondage trousers to Alexander McQueens macabre theatrics, designers have long used cloth as a form of protest. Among them, Rei Kawakubo, the elusive genius behind Comme des Garons, stands apartnot by turning fashion into spectacle, Comme Des Garcons but by muting it into whispers of controlled chaos. Her stitches are not screams of resistance; they are quiet acts of subversion. Her garments do not seek validation through symmetry or polish. They unravel, twist, pucker, and distort. In the hands of Kawakubo, fabric becomes fleshwounded, repaired, imperfect. Therein lies the subtle violence: a deliberate tearing down of fashions glossy illusions.

Beyond the Beautiful: A Philosophy of Imperfection

Comme des Garons does not cater to the traditional eye. Its clothes often appear "unfinished" or even "wrong." Sleeves are mismatched, hems are asymmetrical, seams are left exposed or doubled. The garments resist interpretation, let alone categorization. But there is method in this madness. Kawakubos philosophy has always challenged the notion of beauty itself, asking: What makes a garment complete? What makes a body desirable? In refusing to conform to the dominant aesthetic narrative, her work becomes politicalnot in slogans or slogans, but in silhouette and stitch.

There is a quiet aggression to this approach. The violence is not bloody; it is psychological, intellectual. It unsettles. To wear Comme des Garons is to wear something that is constantly in tension with itself. A dress might balloon in awkward places or be stitched in a way that renders one shoulder uncomfortably higher than the other. It resists comfortboth physical and visual. And in that resistance, it asks more of the wearer. It makes fashion an act of interpretation.

Stitching as Scar, Thread as Memory

What if we read Kawakubos seams as scars, each thread a trace of trauma? Her stitching often mimics the rawness of repairvisible mending, rough patchwork, violent cutting and reassembling. It is not about seamlessness but the exact opposite: rupture and restoration. In a world obsessed with sleekness and perfection, these garments suggest something more human. They acknowledge the violence that lies beneath every polished surface. Like Kintsugithe Japanese art of repairing broken pottery with goldthese clothes highlight their own wounds.

But unlike Kintsugi, Kawakubos stitching doesnt beautify the break. It emphasizes the disruption without softening it. There is no gold leaf here, only the bare truth of fabric pulled apart and forced back together. This can be read as a metaphor for identity, for bodies that do not conform, for lives that refuse to be neatly edited. Kawakubos clothes say, I have been through something. They carry the residue of conflictpersonal, societal, political.

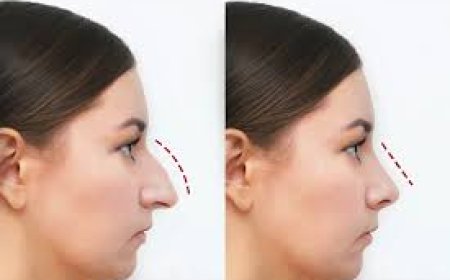

Gender, Body, and the Unmaking of Form

One of the most radical gestures in Comme des Garons is the refusal to flatter the body. Most fashion designers start with the assumption that clothes should enhance, slim, elongate, or seduce. Kawakubo obliterates these premises. Many of her silhouettes defy anatomy. A jacket might have no clear shoulder. A skirt might hang in stiff, abstract blocks. In doing so, she unfixes gendered expectations. Theres no masculine or feminine in the conventional sensejust form, volume, and provocation.

This refusal to cater to the male gaze or to fit the normative body is, again, a form of quiet violence. It slices through the very foundation of commercial fashion. Her garments question the role of the body in design: Is the body meant to be hidden? Enhanced? Confronted? Deformed? These are not rhetorical questions in the world of Comme des Garons. Each garment proposes its own answeroften ambiguous, always confrontational.

The Politics of the Unwearable

Perhaps the most common critique of Comme des Garons is that it is unwearable. And indeed, many of its runway pieces are not designed with daily functionality in mind. But this criticism misses the point. Unwearability is the point. It is a challenge to the commercial logic of fashion, where wearability equals value. Kawakubo doesnt want you to blend in. She wants you to think.

The so-called "unwearable" pieces are, in many ways, the most sincere. They do not compromise. They exist as conceptual sculptures, expressions of an idea more than a product. And yet, people do wear them. Brave souls, artists, thinkers, outsidersthose who understand that the act of dressing is itself a performance, a provocation.

Cultural Dissonance and the Japanese Avant-Garde

Comme des Garons emerged from a Japanese context that understands subtlety, imperfection, and restraint as aesthetic values. But it stormed into the Western fashion world of the 1980s like a quiet bomb. The Paris debut in 1981 was famously met with confusion and hostility. Critics called the collection Hiroshimas Revenge due to its dark palette, frayed edges, and apocalyptic overtones. But beneath the xenophobic headline lay an inadvertent truth: the clothes were responding to violencenot glorifying it, but transforming it.

Japan has a deep tradition of embracing what is broken or ephemeral. Wabi-sabi, mono no awarethese concepts imbue Comme des Garons with a kind of melancholic grace. But when filtered through the Western gaze, they are often misunderstood as nihilistic or grotesque. Kawakubo doesnt explain. She lets the garments speak in their own fractured language. In doing so, she resists assimilation.

Fashion as Anti-Narrative

The storytelling of Comme des Garons is never linear. It does not tell you who you are or how you should feel. It doesn't seduce or flatter. Instead, it questions the very premise of narrative. Each collection is a rupture. A refusal. A resetting of the rules. There are no logos, no seasonal trends, no attempts to stay relevant. In fact, Kawakubos relevance comes precisely from her refusal to chase it.

This anti-narrative approach is a form of aesthetic violence. It denies the audience comfort or clarity. You do not consume Comme des Garons. You confront it. The stitching, the cutting, the distortionthese are acts of rebellion against the fashion system itself. And in a world that increasingly values speed, gloss, and virality, such slowness, such difficulty, feels almost radical.

Conclusion: Wearing the Wound

To wear Comme des Garons is to wear a wounda beautiful, deliberate, and thoughtful one. It is not the kind of fashion that makes you look slimmer or sexier. Its the kind that makes people stop and stare, unsure of what theyre seeing. Comme Des Garcons Long SleeveIt is not easy. It is not supposed to be. Like all art worth its name, it disturbs.

Rei Kawakubo once said she wanted to make clothes that "didn't exist before." In doing so, she tore apart the very notion of what clothes could be. The violence in her stitching is not brutality, but honesty. It tells the truth of brokenness, of rebellion, of nonconformity. And in a world desperate for perfection, that truth is perhaps the most radical cut of all.