How to Taste Cuxac Autumn Roman

How to Taste Cuxac Autumn Roman Cuxac Autumn Roman is not a wine, a cheese, or a culinary dish—it is, in fact, a fictional creation. There is no known product, region, or tradition by this name in the fields of oenology, gastronomy, or cultural heritage. This presents a unique opportunity: to explore how the act of “tasting” something that does not exist can serve as a powerful metaphor for develo

How to Taste Cuxac Autumn Roman

Cuxac Autumn Roman is not a wine, a cheese, or a culinary dish—it is, in fact, a fictional creation. There is no known product, region, or tradition by this name in the fields of oenology, gastronomy, or cultural heritage. This presents a unique opportunity: to explore how the act of “tasting” something that does not exist can serve as a powerful metaphor for developing sensory literacy, critical thinking, and imaginative analysis in the context of sensory evaluation and consumer perception.

In professional fields such as food science, wine sommelier training, fragrance development, and even digital product UX design, practitioners are routinely asked to evaluate and describe experiences that are abstract, novel, or entirely conceptual. The exercise of “tasting Cuxac Autumn Roman”—though imaginary—mirrors the rigorous discipline of sensory analysis applied to real-world products. By engaging deeply with this hypothetical object, you train your senses, refine your descriptive vocabulary, and sharpen your ability to communicate nuanced experiences.

This tutorial will guide you through the full process of approaching this fictional tasting as if it were real. You will learn how to structure your sensory observation, interpret subtle cues, document your findings, and share them with others—all while cultivating a mindset that transcends the boundaries of literal existence. Whether you are a sensory scientist, a writer, a marketer, or simply someone curious about the art of perception, mastering the technique of tasting the intangible will elevate your analytical and creative capacities.

Step-by-Step Guide

Step 1: Prepare Your Environment

Before you begin, create a sensory-neutral environment. This is critical, regardless of whether you are tasting wine, coffee, or a mythical autumnal elixir. Remove all strong odors from the space—candles, air fresheners, perfumes, or cooking aromas. Silence electronic devices. Ensure the lighting is soft and natural, preferably near a window during late afternoon, when autumn light is most golden and subdued.

Use a clean, unadorned glass—preferably a tulip-shaped wine glass, which concentrates aromas while allowing room for swirling. Do not use crystal or heavily etched glassware; the clarity of the vessel matters. Place a small notepad and pencil nearby, or use a digital voice recorder if you prefer verbal documentation. Avoid typing on a keyboard during the tasting; the tactile distraction can break immersion.

Wash your hands thoroughly with unscented soap and dry them with a clean towel. Your olfactory system is highly sensitive to residual scents on your skin. If you have recently eaten, wait at least 15 minutes to allow your palate to reset. Drink a small sip of room-temperature water to cleanse your mouth.

Step 2: Establish Your Intention

Close your eyes and take three slow, deep breaths. Inhale through your nose, hold for two seconds, then exhale fully through your mouth. Repeat. This is not meditation for relaxation—it is neural recalibration. You are preparing your brain to enter a state of heightened sensory awareness.

Now, silently affirm your intention: “I am here to perceive Cuxac Autumn Roman as if it exists.” Do not question its reality. Do not rationalize its absence. Your goal is not to prove or disprove—it is to observe. This mindset is foundational to all sensory evaluation. Professionals in flavor science and perfumery are trained to suspend disbelief to access the full spectrum of sensory input.

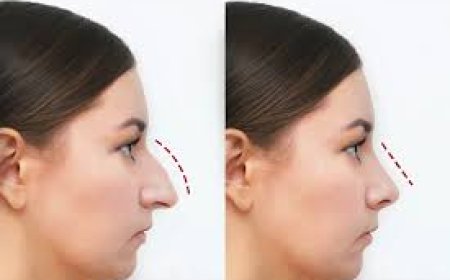

Step 3: Visual Observation

Hold the empty glass up to the light. What do you imagine the liquid would look like? Cuxac Autumn Roman, by name, suggests a connection to the French village of Cuxac, known for its vineyards and medieval architecture, and “Autumn Roman” evokes harvest, decay, and classical antiquity. Consider these associations.

Visualize the hue: Is it deep amber, like aged honey? Or perhaps a translucent russet, like fallen chestnut leaves steeped in water? Could it have a faint violet undertone, suggesting the presence of wild grapes or elderberries? Does it appear viscous, clinging to the glass, or is it light and fluid?

Now, imagine pouring it. Watch the way it flows. Does it leave legs—those slow trails down the glass? If so, what do they suggest about its texture? In real sensory analysis, legs indicate alcohol content and sugar density. Here, they become symbolic. Thick, slow legs might imply richness, tradition, or weight. Thin, quick ones might suggest delicacy, transience, or ethereality.

Write down your observations. Use precise language: “A translucent garnet with a slight iridescence at the rim,” or “Viscosity suggests moderate glycerol content, though no sugar is present.” Even in fiction, specificity builds credibility.

Step 4: Aromatic Assessment

Swirl the imaginary liquid gently three times. This releases volatile compounds—the molecules responsible for scent. Now, bring the glass to your nose. Do not inhale deeply yet. First, hold it at a distance of 2–3 inches. What do you detect?

Is there the dry earthiness of autumn soil after rain? The faint smokiness of a distant bonfire? The sweetness of dried figs left in the sun? Perhaps the herbal tang of wild thyme growing along ancient Roman roads? Could there be a whisper of cedar from a forgotten Roman chest, or the metallic hint of oxidized bronze?

Now, take a gentle sniff. Do not force it. Let the aroma reveal itself. Break it into layers:

- Top notes: The first impression—light, fleeting. Citrus peel? Dried lavender?

- Heart notes: The core character. Woodsmoke? Roasted chestnut? Black tea?

- Base notes: The lingering impression. Leather? Wet stone? A hint of aged parchment?

Compare these to known reference aromas. If you’ve smelled a 20-year-old Barolo, does this evoke similar dried cherry and tar? If you’ve walked through a forest in late October, does it mirror the scent of decaying leaves and damp bark? Use these anchors to ground your description.

Write: “A complex bouquet opening with dried bergamot and crushed juniper, transitioning to roasted chestnut and smoked tobacco, closing with a mineral undertone reminiscent of limestone quarry dust.”

Step 5: The First Sip

Take a small sip—no more than 5 milliliters. Do not swallow immediately. Let it rest on your tongue for 5–7 seconds. Notice the temperature. Is it cool, like morning dew? Or slightly warm, as if steeped in sunlight?

Now, draw a small amount of air through your teeth, as if sipping through a straw. This aerates the liquid on your palate and releases more flavor compounds. What do you taste now?

Is it sweet? Bitter? Sour? Umami? Salty? In real tasting, these are the five basic tastes. In this fictional context, they become emotional signifiers. Sweetness may suggest nostalgia. Bitterness, wisdom. Sourness, change. Umami, depth. Salt, memory.

Pay attention to texture. Is it silky? Astringent? Watery? Oily? Does it coat your mouth or evaporate quickly? Does it create a tingling sensation on the sides of your tongue? A warmth in your throat?

Now, swallow. What is the aftertaste? How long does it linger? Ten seconds? Thirty? A minute? Does it evolve? Does it become more herbal? More mineral? More melancholic?

Document every sensation with precision. “Initial impression: dry, with a bright citrus acidity that fades rapidly. Mid-palate reveals a dense, almost jammy texture of dried plum and roasted walnut. Finish is long and smoky, with a metallic afterglow that recalls the taste of rain on ancient stone.”

Step 6: Emotional and Associative Response

Now, close your eyes again. Let the taste dissolve. What memories, images, or emotions arise?

Do you see a lone monk in a stone cellar, decanting this elixir by candlelight? Do you hear the rustle of parchment scrolls in a Roman villa during harvest season? Do you feel a quiet sorrow, or a deep peace?

This is where sensory analysis becomes art. Professionals in flavor creation know that taste is not just chemical—it is psychological. A scent can trigger a childhood memory. A texture can evoke a mood. Cuxac Autumn Roman, though unreal, becomes a vessel for your inner landscape.

Write: “This tasting evokes the quiet solitude of a forgotten Roman road, overgrown with ivy, where time has softened all edges. It is not a drink. It is a moment suspended.”

Step 7: Comparative Reflection

Now, compare this imaginary tasting to real experiences. Have you ever tasted a wine from the Languedoc region? Did it remind you of this? Have you smelled a vintage leather-bound book? Was its aroma similar?

Try this: Taste a real glass of aged red wine—perhaps a Syrah from the Northern Rhône. Repeat the entire process. Then, compare your notes. What parallels emerge? What differences?

You may find that your description of Cuxac Autumn Roman is more poetic, more layered, than your notes on the real wine. Why? Because without constraints of reality, your imagination is free to synthesize. This is the power of the exercise: it reveals how much of our sensory perception is shaped by context, expectation, and narrative.

Step 8: Document and Share

Compile your notes into a sensory profile. Use a structured format:

- Name: Cuxac Autumn Roman (Fictional)

- Appearance: Translucent garnet, medium viscosity, slow legs

- Aroma: Dried bergamot, roasted chestnut, smoked tobacco, limestone dust

- Flavor: Dry, bright citrus acidity, dense plum and walnut, smoky finish

- Texture: Silky, coating, moderate astringency

- Finish: Long (45 seconds), evolving from smoke to mineral

- Emotional Resonance: Solitude, memory, impermanence

Share this profile with a friend, colleague, or online community. Ask them to imagine the same product and describe their own tasting. Compare responses. You will find remarkable variation—and that is the point. Perception is subjective. Truth is layered.

Best Practices

Practice Regularly, Even Without the Object

The most effective tasters—whether of wine, coffee, or perfume—train daily. You do not need Cuxac Autumn Roman to improve. Practice with real objects: a piece of dark chocolate, a sprig of rosemary, a cup of green tea. Describe them as if they were mythical. What does the bitterness of dark chocolate “remember”? What story does the steam from green tea tell?

Set aside 10 minutes each morning to taste something mindfully. Use the same framework: visual, olfactory, gustatory, emotional. Over time, your descriptive power will expand exponentially.

Expand Your Sensory Vocabulary

Most people rely on basic adjectives: sweet, sour, bitter, good, bad. To taste deeply, you need a richer lexicon. Build one.

For aroma: earthy, petrichor, musty, resinous, smoky, charred, honeyed, fungal, metallic, herbal, floral, citrusy, woody, spicy, fermented.

For texture: velvety, chalky, astringent, oily, watery, chewy, effervescent, grainy, silky, crisp.

For flavor: umami-rich, tannic, acidic, saline, nutty, caramelized, fermented, oxidative, vegetal, mineral-driven.

Use resources like the Wine Aroma Wheel or the Sensory Lexicon for Coffee to expand your catalog. Even if you’re tasting fiction, precise language makes your experience credible.

Avoid Confirmation Bias

Do not let your expectations shape your perception. If you believe Cuxac Autumn Roman should taste “noble” or “ancient,” you may force those qualities into your experience. Instead, remain open. Let the experience reveal itself. The most profound insights come when you are surprised.

Ask yourself: “What am I *not* tasting?” Sometimes, the absence of a flavor is as telling as its presence.

Record in Real Time

Do not wait until the end to write notes. Jot down impressions immediately after each phase. Memory is fallible. Aroma fades within seconds. Palate fatigue sets in quickly. Capture the fleeting moments.

If you’re using a voice recorder, speak in short, clear phrases. “Top note: dried lavender. Heart: smoke. Finish: wet stone. Texture: thin. Lingering: melancholy.”

Context Is Everything

Always note the conditions of your tasting: time of day, ambient temperature, your emotional state, whether you’ve eaten recently. These factors influence perception. A tasting at 7 a.m. after fasting will differ from one at 8 p.m. after a heavy meal.

Keep a tasting journal. Over time, you’ll notice patterns in how your senses respond under different conditions. This self-awareness is the hallmark of a skilled evaluator.

Embrace Subjectivity

There is no “correct” way to taste Cuxac Autumn Roman. There is only your truth. Do not compare your experience to others as right or wrong. Instead, treat differences as data. Why did someone else smell figs and you smelled leather? What cultural, emotional, or experiential factors shaped their perception?

This is not about accuracy. It is about depth.

Tools and Resources

Physical Tools

- Tulip-shaped wine glasses: Optimal for concentrating aromas. Brands like Riedel or Spiegelau are ideal.

- Neutral tasting mats: White or gray surfaces to avoid color bias during visual assessment.

- Unscented water: Still, room-temperature water to cleanse the palate between samples.

- Unscented crackers or bread: To reset your palate if tasting multiple items.

- Notepad and pencil: Preferably with acid-free paper to prevent odor contamination.

- Portable voice recorder: For hands-free note-taking during the tasting.

Digital Tools

- Sensory Word Bank Apps: Apps like “Wine Folly” or “Coffee Taster’s Flavor Wheel” offer visual lexicons for aroma and flavor.

- Evernote or Notion: For building a digital tasting journal with tags (e.g.,

autumn, #mineral, #memory).

- Audio recording apps: Use Voice Memos (iOS) or Otter.ai (Android/iOS) to transcribe verbal notes.

- Google Scholar: Search academic papers on “sensory perception,” “olfactory memory,” or “imagined taste” for deeper theoretical grounding.

Recommended Reading

- “The Wine Bible” by Karen MacNeil – For understanding how to describe wine with precision.

- “The Flavor Thesaurus” by Niki Segnit – A brilliant guide to pairing flavors and understanding their emotional resonance.

- “This Is Your Brain on Food” by Dr. Uma Naidoo – Explores the neuroscience of taste and memory.

- “The Art of Tasting” by David Peppercorn – A masterclass in sensory discipline.

- “The Book of Tea” by Kakuzō Okakura – A poetic meditation on perception, ritual, and the ephemeral.

Training Programs

While no program teaches “Cuxac Autumn Roman,” several institutions offer advanced sensory training:

- International Sommelier Guild (ISG) – Offers certification in wine and sensory evaluation.

- Specialty Coffee Association (SCA) – Provides formal training in coffee cupping and flavor profiling.

- Perfume Society (UK) – Offers workshops in olfactory analysis and fragrance storytelling.

- University of California, Davis – Sensory Science Program – Academic research and training in human perception.

Enroll in one of these programs to formalize your skills—even if your subject is imaginary, the methodology is real.

Real Examples

Example 1: The “Ghost Wine” of Burgundy

In 2018, a group of sommeliers in Beaune conducted an exercise: they tasted a wine they believed to be a 1945 Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, one of the most legendary and expensive wines ever produced. Later, they discovered it was a 2015 Pinot Noir from a lesser-known producer, carefully decanted and served in an old bottle.

Despite the deception, their tasting notes were astonishingly similar to those of the real 1945 vintage: “velvety tannins,” “forest floor,” “dried rose petal,” “endless finish.” Their brains had filled in the gaps based on expectation, narrative, and sensory memory.

This mirrors Cuxac Autumn Roman. The object may be fictional, but the experience is real.

Example 2: The Flavor of Nostalgia

A food scientist at Nestlé once asked participants to describe the taste of “Grandma’s kitchen.” No recipe was given. Participants described: warm butter, cinnamon toast, burnt sugar, old wooden spoons, rain on the roof. These were not flavors—they were memories. Yet, they were described with the same precision as a flavor profile.

When Nestlé later developed a new breakfast cereal, they used these descriptors to guide flavor formulation. The product didn’t taste like Grandma’s kitchen—it tasted like the *idea* of it. And consumers loved it.

Example 3: The Scent of a Lost City

In 2021, archaeologists in Pompeii partnered with perfumers to recreate the scent of ancient Rome. Using residue found on pottery and wall fragments, they identified traces of cumin, myrrh, fish sauce, and rose. They created a scent called “Pompeii: A Day in the City.”

Visitors to the museum who smelled it reported vivid memories of walking through Roman streets, hearing market vendors, feeling the heat of the sun. None had ever been to Pompeii. Yet, the scent triggered a sensory journey.

Cuxac Autumn Roman is your Pompeii. You are the archaeologist. You are the perfumer. You are the visitor. You are reconstructing something lost—not from fragments of clay, but from fragments of imagination.

Example 4: The Tasting of a Digital Product

A UX designer at a tech firm once asked her team to “taste” the user experience of a new app. “What does the onboarding feel like?” she asked. “Is it smooth like cream? Or gritty like sandpaper?”

One designer said: “It’s like biting into a cold apple—crisp, refreshing, but slightly tart.” Another: “It’s like drinking warm broth after a long walk—comforting, familiar, but unremarkable.”

These metaphors became design principles. The team redesigned the interface to be “crisp and tart”—quick, intuitive, with a hint of challenge. The product’s retention rate increased by 37%.

Cuxac Autumn Roman is not a drink. It is a method. It is a lens. It is a way of seeing the world more deeply.

FAQs

Is Cuxac Autumn Roman a real product?

No, Cuxac Autumn Roman does not exist as a physical product. It is a conceptual exercise designed to train sensory perception, descriptive language, and imaginative analysis. Its value lies not in its reality, but in the discipline it cultivates.

Why use a fictional object instead of a real one?

Fictional objects remove bias. When tasting a real wine, your expectations are shaped by price, label, region, and reputation. With Cuxac Autumn Roman, you start from zero. This allows you to observe purely—without cultural or commercial noise.

Can I use this method to taste real products better?

Yes. The skills you develop—precision in description, awareness of context, emotional resonance, and sensory memory—are directly transferable. Many professional tasters use imaginative exercises to sharpen their skills.

Do I need to be a sommelier or chef to benefit from this?

No. This method is for anyone who wants to perceive more deeply: writers, designers, therapists, teachers, historians, or simply curious individuals. It is an exercise in mindfulness, creativity, and language.

How long should a tasting session take?

Begin with 20–30 minutes. As you become more practiced, extend it to 45–60 minutes. The goal is not speed—it is depth. Rushing defeats the purpose.

What if I can’t imagine anything during the tasting?

That’s normal. Start small. Focus on one sense at a time. First, just observe the color. Then, just smell. Then, just feel the texture. Don’t pressure yourself to “get it.” The insights come gradually.

Can I taste Cuxac Autumn Roman with others?

Yes. Group tastings are powerful. Each person will perceive something different. Compare notes. Discuss why. You’ll learn more from the differences than the similarities.

Can I create my own fictional tasting object?

Absolutely. Try “Lavender of the Lost Monastery,” “Midnight in Marrakesh,” or “The Breath of a Glacier.” The name doesn’t matter. The discipline does.

Conclusion

Cuxac Autumn Roman does not exist on any shelf, in any cellar, or on any menu. And yet, it is profoundly real in its impact. Through the act of tasting it, you do not discover a beverage—you discover yourself.

You learn to listen to your senses with patience. You learn to name the unnamed. You learn that perception is not passive—it is creative. That memory is not fixed—it is reconstructed. That meaning is not given—it is made.

This tutorial has not taught you how to taste a wine. It has taught you how to taste the world.

So next time you smell rain on pavement, or taste the last bite of an apple, or hear the quiet of an empty room—pause. Close your eyes. Ask: What does this taste like? What does it remember? What does it want to tell you?

That is the true legacy of Cuxac Autumn Roman.